Dec 22, 2025 · 6 min read

What Building a Tiny Transformer Taught Me So Far

Lessons from implementing a character-level Transformer and probing what actually matters

I’ve been implementing a small, character-level Transformer from scratch to build intuition for how these models behave in practice. For training data, I used a single short text: A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway.

The model itself was intentionally small but non-trivial: 5 Transformer layers, 8 attention heads, d_model = 128, and d_ffn = 512, for a total of roughly 1 million parameters. This kept iteration fast while still exhibiting real optimization behavior.

One constraint I imposed was avoiding existing Transformer implementations altogether. I wanted to confront the implementation details directly rather than inherit them from a reference implementation, so that the failure modes would be mine, not copied.

I implemented the model incrementally, starting from small components like the character tokenizer and attention modules, and then composing them into Transformer blocks and a training loop. I later consulted ChatGPT for specific parts to clean things up or adopt more idiomatic patterns—for example, using torch.tril with masked_fill for causal masking instead of a hand-written loop.

Along the way, I ran a series of small ablations. None of these results are novel, but several were unintuitive to me until I saw them empirically.

1. Initialization mainly affects early optimization, but leaves a long tail

I initially used PyTorch’s default weight initialization. While nn.Linear layers use a reasonable fan-in–scaled heuristic, PyTorch initializes nn.Embedding weights from a normal distribution with standard deviation std = 1.0. This is massive compared to the GPT-style initialization of std = 0.02.

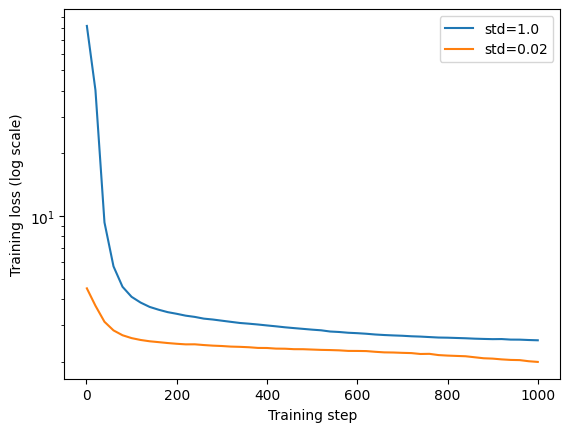

The first thing I noticed was that the training loss at step 1 was extremely high (around 80), far higher than I expected for a character-level language model. After some investigation(and a nudge from ChatGPT)I reran the experiment using a GPT-style initialization with Gaussian weights and std = 0.02 applied consistently. Figure 1 shows the resulting training loss curves on a log-scaled y-axis.

Figure 1: Training loss vs. step (log-scaled y-axis) comparing default PyTorch initialization (with

nn.Embeddingatstd = 1.0) and GPT-style initialization (std = 0.02).

With the default initialization, the initial loss was enormous but collapsed rapidly within the first few dozen steps. With std = 0.02, training started at a much more reasonable loss and progressed smoothly from the beginning.

While the gap narrows quickly, it does not disappear immediately. Even after 1000 steps, the run with std = 0.02 still achieves a consistently lower loss. Both runs appear to converge toward similar values eventually, but the poorly scaled initialization leaves a noticeable optimization tail.

This behavior is consistent with a known effect: high-variance embeddings produce high-variance activations in the first layer, which then propagate forward, saturating the softmax and inflating the initial loss. Although gradients eventually rescale activations, the early instability can influence optimization longer than one might expect.

2. Positional embeddings aren’t required to overfit a small corpus

Removing positional embeddings entirely did not prevent the model from reaching very low training loss.

At this scale, attention effectively degrades into a sophisticated Bag-of-Words–like aggregation over the context window. The model leans heavily on character co-occurrence statistics and learns something closer to: given the multiset of characters seen so far, what character is likely next?

This is sufficient for memorizing a small dataset. I don’t expect it to generalize. On larger corpora, where syntax, word order, and long-range structure dominate, positional information should become essential.

3. Untying embedding and output weights made little difference

I also tried untying the token embedding matrix from the output projection matrix. For this tiny character-level model trained to overfit a small dataset, the effect was negligible.

In hindsight, this makes sense. Weight tying mainly acts as a regularizer and a parameter-efficiency mechanism. With a small vocabulary and ample capacity, neither is a limiting factor.

I expect this choice to matter more at larger scales, especially when embeddings are expected to encode richer semantic relationships.

4. Residual connections are critical for trainability in deeper models

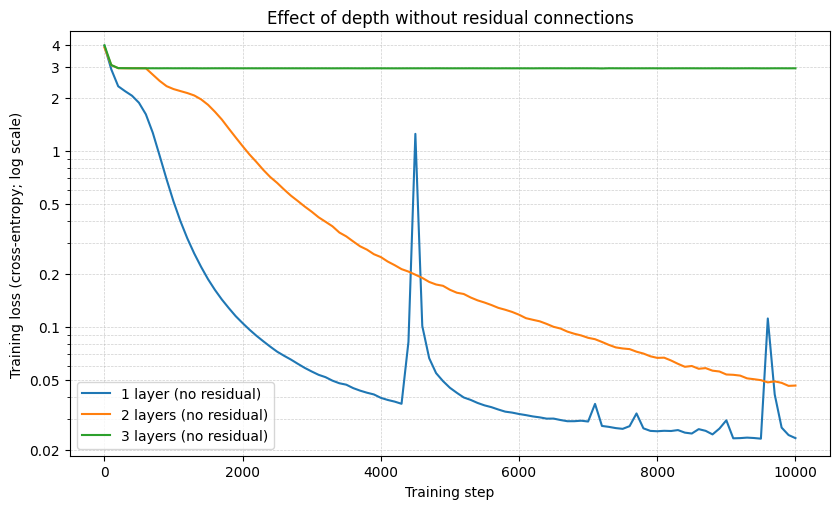

As another ablation, I removed residual connections and varied only the number of Transformer layers. Figure 2 shows the training loss (log scale) for 1-, 2-, and 3-layer models trained without residual connections.

Figure 2: Training loss vs. step (log-scaled y-axis) for models trained without residual connections. Increasing depth rapidly leads to optimization failure.

With one Transformer block, training proceeds normally and converges quickly. With two blocks, learning is noticeably slower but still makes steady progress. With three blocks, training fails almost entirely: loss remains near its initial value and shows no meaningful improvement.

Without residual connections, gradients must propagate through a deep chain of nonlinear transformations, quickly pushing the model into a vanishing-gradient regime. Residual connections provide identity paths that stabilize optimization and allow deeper models to remain trainable.

This experiment made it clear that residual connections are not just a convenience. They become critical for trainability once depth increases.

A pattern across these experiments

Across these ablations, a consistent pattern emerged. Many Transformer components aren’t strictly required to overfit small datasets. They become important once depth increases, scale increases, or the optimization problem becomes harder.

Small models are forgiving. Larger models are not.

This makes it easy to underestimate why certain architectural conventions exist until you cross the regime where they suddenly become indispensable.

What’s next?

All the code for these experiments lives here:

https://github.com/kikim00/mini-gpt

Implementing a Transformer from scratch turned out to be a very rewarding experience. Watching the model evolve from producing pure nonsense to generating vaguely English-like text, and eventually memorizing parts of the training corpus in its weights, made many abstract concepts feel concrete in a way that reading papers alone never does.

As next steps, I plan to:

- Run a few more ablations, such as comparing pre-LN vs. post-LN Transformer blocks

- Train on more diverse text to see which observations continue to hold

- Implement KV caching to better understand inference-time efficiency and trade-offs

I’ll likely continue to use this repo as a sandbox for small, focused experiments and write down what I learn along the way.